Optimizing Investment Sizing with the Kelly Criterion

Chris Sparks demonstrates how to use the Kelly Criterion, aka "Fortune's Formula," to determine how much of your bankroll to invest into a lucrative investment opportunity.

Video recording above; resources mentioned and full transcript below.

Resources mentioned:

Experiment Without Limits (peak performance workbook)

“The Kelly Criterion” (a straightforward explanation if you’re unfamiliar)

Transcript:

Note: transcript slightly edited for clarity.

Tom: Welcome one, welcome all. We have the inimitable Chris Sparks with us today talking about the Kelly Criterion and lessons from Pro Poker. Chris is, to put it mildly, a ringer. Just a phenomenal, phenomenal poker player. I think he may be hosting a poker social later in ODI. Do be very careful when you play with Chris, because as I think he'll probably allude to, his track record speaks for itself. But without further ado, Chris, the floor is yours, and I for one am excited for this session, and I'm buckled up and ready to rock and roll.

Chris: Thanks. Hey, guys. Thanks for the wonderful introduction, Tom. I'm excited to be here. If I'm looking in the opposite direction, it's because my webcam is broken, so I'm on my phone and my laptop. So excuse that. And this is all so exciting, because I don't think I've made a PowerPoint since I left college a little over a decade ago, so it was kind of fun to figure that out. So this kind of session got started by request. It was a conversation in Slack about Kelly Criterion as something that people were interested in learning.

And I don't think that I would consider myself an expert in it, but what I do think I am an expert in is sizing bets, which I think is a very, very, very underrated skill as an investor. Right? Obviously, you need to find good opportunities to invest in, get access to those, but I think that knowing how much to bet is a very critical skill. Having an understanding of what is your edge, what do you think you will have as an average outcome across the varying permutations of reality, and having the ability and conviction to size correctly, I think, is something that is very important to understand. And the best mental model that I have found for this is a formula called the Kelly Criterion.

So, I'm gonna walk you through a quick case study on something that I used this for last year with the 2020 election, and then I think my presentation will be about fifteen minutes, and then we'll open up the floor for any questions that you guys have.

So, let's see if I can figure out how to move. Yeah. So here is a little bit about me. I'm most known as a poker player. So over the past sixteen years, I've played about two million hands of poker. For about ten of those years I was either a part-time or full-time pro poker player, and my claim to fame when I was at my career peak (this was right before the event we call Black Friday, where poker got shut down in the U.S.—my first retirement, if you will) I was ranked in the top twenty online cash game players in the world, where it was actually very difficult for me to find someone who was willing to play me. These days, my primary focus is I have a training company called Forcing Function where we do what I call "Peak Performance Architecture." So I work with about twelve clients at a time, primarily active investors, have hedge funds, VC, et cetera, as well as executives of big tech companies to maximize their personal professional outcomes.

I do have a pretty long waitlist. I think my next availability is October, but we're leading a group class. This would be our third cohort. It's called Team Performance Training. That's teamperformancetraining.com, if you want to check that out.

Me as far as an investor, I do some things that are somewhat normal, and then some things that are not so normal. So obviously I'm involved in the public markets, both as a kind of portfolio allocator, but as well as making some single-name bets. I invest in some VC and micro-PE funds. I have some collateral loans, both fiat and crypto-based, as well as a pretty substantial crypto portfolio. Primarily the large caps, but some alts as well. The not-so-normal stuff: so, I've backed a lot of poker players, primarily for cash games but some tournaments, as well as some daily fantasy sports players. And I like to make lots of random bets. So these are anything from laying odds on half-court shots to, as we're going to see, betting on elections. I think that people have a far-too-narrow view of what can count as investing, and you should thinking about how your unique background and experience gives you access to opportunities to deploy capital, financial and otherwise, that others might not have access to. Right? You don't need to be betting on the same thing that everyone else is betting on. You have some proprietary information and access, so, taking advantage of that.

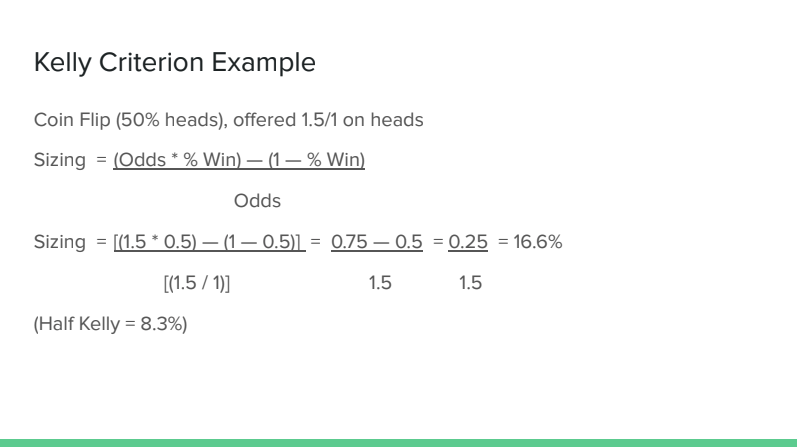

So here is the Kelly Criterion formula. And don't let the math scare you. It is actually very simple. So, first, what this formula is trying to output is bet sizing. And this is denoted as a percentage of your bankroll. Right? So if your answer is ten, that means that you can be betting up to 10% of your bankroll. How do you calculate that? The simplified version is Edge over Odds, or as I like to say, Expected Value over Odds. Expected value: This is something that we talk about in poker all the time, this is the primary mental model. If you don't know or understand it, highly recommend you look it up. Expected value is, on average how much do you expect to make by making this bet. Right? So you can see how that's calculated, right? When you think about expected value in the abstract, it's, "If this goes well, what's the percentage chance of that, and how well does it go? If it doesn't go well, how often does that happen?" Right? Minus one, minus the percentage chance of winning, and then how well does that go?

And then all of that is divided by the odds that you are getting. Right? So, two to one means that if you are betting a hundred, you get two hundred, if you win. One to two means that if you bet a hundred you get fifty if you win. Obviously, the better odds that you are getting, the more you should be betting. And so those are the odds that you are receiving from the counter party. And it's notable, that this output is for full-Kelly. And you generally never go full-Kelly unless you're a total madman and you're burning down the boats. The general rule is that you want to bet between .3 Kelly and .5 Kelly. So you can see the implications of that—Exactly, Kyle. I was gonna say, "Never go fully Kelly." But didn't want to go there. If you bet the .3 Kelly, you are getting 50% of the upside, but with only 10% of the variance. So this is like, you should be betting at least this much. Right? You are eliminating 90% of the downside, and you're keeping 50% of the upside. On the other hand, you generally don't want to be going above half-Kelly. And so, with half-Kelly, you're getting 75% of the upside, but only having 25% of the downside.

So let's do a really, really simple example for you guys to get this, and then I'll get into a quick case study. Whoops. Too far. There we go.

So in our example, we are encountering a very friendly gentleman on the road who wants to flip a coin. And so obviously we are assuming that this is a fair coin. Right? We get into implications here, right, where if someone offers you something that's too good to be true, it might be. So if he says, "I will give you 1.5 to 1 if this is a head." And you assume that it's a fair coin, this is a bet that you should take every time. Right? There's some judgment on like, "How honest is this?" If it comes up tails three times in a row, you might start to doubt the fairness of the coin, like, "Okay, maybe I wanna supply the coin." Or maybe, "Let me choose what it's going to be when it's in the air." This type of stuff. But let's assume it's a fair coin, so it's going to come up heads 50% of the time. And if you win, let's say you're betting a hundred dollars, each time it comes up heads he will give you one fifty. Right? So if you win you get a hundred fifty bucks, if you lose, you lose a hundred.

So we can see how this calculates out, right? The odds. This is 1.5, right? 1.5 divided by 1 times our percentage chance of winning. Right? It's coming up heads 50% of the time. And then we're going to subtract one minus the 50% chance of winning. Right? We lose 50% of the time. Right? So that's 1.5 times 50%, that's .75, 1 minus 0.5 is 0.5, and so that comes out as 0.25 on the top. All of that is divided by the odds that we are being offered. Right? So being offered 1.5 to 1. So, we divide by 1.5. This means that if someone is offering us this bet, the full-Kelly sizing here would be we bet 16% of our bankroll. Right? This is a very, very good bet for us. And as you can see, the better odds that we are being offered, the larger this sizing goes. So we would probably be betting half-Kelly, which would be 8.3% of our bankroll. And the nice thing about how you can see how this goes is like, as our bankroll increases we continue to bet more. Right? Our capital compounds. But if we are doing this, we never go broke, because if we lose, we start to bet less.

Right? This is a counter to what a lot of people do in the real world: when they make more money, they want to protect it and they start betting less, and when they start losing money, they want to get that money that they lost back, so they start betting larger. The optimal is to bet as a fraction of your investable capital.

Yes, Brendan. This is based on taking the bet one single time. And so you can see, each time that you take the bet, say this is an iterated game, you're going to adjust for your bankroll size. But the percentage chance of your bankroll, assuming your assumptions don't change, remains the same.

So let's get into a little case study here. I happen to think that election betting is massively inefficient. I've done very, very well in the last three elections, and usually the biggest limiter is just how much capital I can put to work. It usually requires me spreading action across a number of exchanges, using crypto of varying shadiness. But the infrastructure was relatively built out in 2020, so I was able to deploy as much as I wanted. And when a lot of people look at election betting, right, just like a lot of things in life, everyone is betting on the things that everyone is talking about. Everyone's talking about what's the valuation of Fang or Tesla, or looking at the general election because that's what everyone is talking about. But the most inefficient markets are the things that not everyone is going after. Right?

If you're a sports better, the Super Bowl can be inefficient because you have a lot of retail action, but generally, those games are very well-studied. Right? For the best edge in sports betting, you're looking for, like, college lacrosse, or golf. As Tom says, the blue oceans, the biggest edge are the places that aren't as competitive. So, for election betting I find that the state-by-state elections offer the best potential for edge, because we have a lot of information and there's fewer compounding probabilities. Right? We're looking at a single election, versus like the general election, due to the Electoral College, all of these things need to happen concurrently, and there's a lot of correlations there.

So, I zeroed in on two elections in particular. Texas for Trump to win, and New Hampshire for Biden to win. As you can see, in both of these elections Trump is heavily favored in Texas, and Biden is heavily favored in New Hampshire. But because people generally want to bet on the underdog, right, everyone wants to bet a hundred to win a thousand, I find that the odds that are near sure-thing actually offer our best opportunity for edge, because no one likes, for example, betting three hundred fifty to win a hundred. Everyone is biased towards the underdog. So, data that I was looking at, to determine, "Hey, how good do these races look for the favorites?" First was the 2016 results. So, New Hampshire was kind of a toss-up that actually went for Hillary in 2016, but Texas went dramatically for Trump. Right? So all things being equal, you assume that to continue. There was a lot of media narrative around, "Hey, everyone from the coast is moving to Austin," et cetera, but you assume that the baseline is going to be around ten percent.

Polling, right? Five Thirty-Eight, et cetera, there's lots of thoughts on how accurate these polls are, but you can see within a large margin of error, things were looking very, very good for the favorites. Right? Texas was coming in a +4 for Trump, New Hampshire was coming in at a whopping +8%. For New Hampshire. In fact, there was not a single poll leading up to the election that did not have New Hampshire going for less than 4%. So, large margin of error. Notable, between 2016 and 2020 there were large demographic shifts in both of these states. So, in Texas, there was a large Latino population increase of 15%, and based on polling, this population leaned heavily Republican. And then in New Hampshire, there was a 20% increase in the voter base, and of this increase in the voter base, it skewed very young and much more of a minority tilt. Right? New Hampshire is 90% white, and this was taking it to 80% white. It was a pretty big shift when you're talking about the small margin of error winning.

And then finally, something that a lot of people under-appreciate, especially in 2020, due to COVID, a lot of the votes were already counted. Over 25% of the voting in both of these states was already counted before the election, and in early voting, it was +16% in New Hampshire and +10% in Texas. And this is especially good in Texas, because early voting tends to favor Democrats due to people in urban areas tending to vote early at a higher proportion. So all the numbers are looking very good for these two bets.

So we were offered the same odds on both of these. It's -350 or 1 to 3.5. So this means that I am laying 350 to win 100. And this means that the market is saying that Trump and Biden, respectively, should win about 78% of the time.

Now, based off of the data that I showed you on the last slide, I thought that this was too low. That although they were already favorites, I thought that they were overwhelming favorites. And so my true estimate was that it was 1 to 9, or that the favorite's going to win 90% of the time. And my lower bound, saying like, "If I use very conservative assumptions," I was very confident they were going to win at least 83% of the time. So, presumably, the market was underpricing these favorites.

But the question for me is like, "Is this edge large enough to justify betting on, and if so how much should I bet?"

So I'm gonna hit escape here and bring up a little calculator. So you can see, here's our example before. Our simple example. 50% probability of winning a coin flip, we're offered 1.5 to 1. Let's say we have a hypothetical one million dollar bankroll, and we're betting half-Kelly. So this means that we should bet 8% of our bankroll, or eighty-three thousand dollars each time that this bet is offered to us.

Now, we're going to calculate here what I just laid out. So, odds of winning, .83, right? 83%. I'm gonna go back here. Yeah. So my lower-bound estimate, right, if I'm being really conservative, I think that the favorite was gonna win 83% of the time. So I put in my odds of winning at 83%. The odds that I'm receiving are 1 divided by 3.5, right? Because I'm betting on the favorite. And then we're adjusting on Kelly. Remember, we're using a discount here of .3. And so we calculate.

So, using conservative assumptions, I should be betting at least 7% of my bankroll, or 70k, on a one-million-dollar bankroll.

Now, if we change these assumptions to be a little bit more aggressive, so we say, "All right, I actually think the odds are 90%, and I'm gonna bet half-Kelly, because I'm a poker player, I like to gamble." And so this gets a little crazy. All of a sudden you can see on each of these two elections, I should be betting 27% of my bankroll. So, between these two bets, I'm putting over half of my net worth into play.

Now, I did not do that. I thought that was a little crazy. But what I did do, right, the lower bound. I should be betting at least 7% of my bankroll, and this limit should be up to 27% of my bankroll.

Now, one consideration is that this is a bit of a pairs trade. I'm betting on Biden in one state and I'm betting on Trump in one state, and usually, if there's a bias in this data, it's gonna be in favor of one candidate or another. So, it's unlikely that I lose both of these. If my assumptions are off, they're going to be off in one direction or the other. So any deviations are somewhat offset. So I can be a little bit more aggressive than I would be if I was betting only one of these, or for example, if I was betting on Trump in two states instead of betting on one candidate in each state.

And so what I actually do, I bet .5 Kelly at the lower bound. So, escape here, we can calculate that. So the lower-bound probability is, okay, I know it's at least eighty-three, and I'm betting half-Kelly. So that tells me to bet 11% of my bankroll on each of these bets. Which is what I did. I bet 22% total of my bankroll, and I ended up winning both, which was a lot of fun. I did have to bet those in Eth, and so I would have actually been a lot better holding the Eth, but couldn't have known that at the time.

So, implications of Kelly Criterion. Kelly represents the limit of rational bets. You can bet up to this level. It does not calculate the probabilities, it does not calculate the payoffs, or actually tell you how much you should bet. This is a limit, right? You should bet at least .3 and no more than .5. Where you go in that range, or you could go obviously less than .3 if you're feeling conservative, or more than .5 if you're gamble-gamble. It does not tell you what you should actually do.

Factors that you need to account for in order to decide how much to actually bet: first, accounting for the uncertainty of your edge. Assume, always, that you will overestimate your edge. Your level of control over the outcomes. Right? If you are betting on yourself, you have a lot more control than if you're betting on public markets or crypto, et cetera. You're betting on a complex system. There's just a lot of unknown factors. What is the reliability of your information? So, there's like—polls. How much do I trust those? Early voting data? How reliable is that? Do these demographic shifts really matter? Those are the types of things I'm trying to think about.

Examples that are used for Kelly Criterion are: you get a hot tip on a horse at the race track. Like, "Hey, this horse is in heat and it really wants to get to the finish line," or, "This horse has a gimp leg and is never gonna make it." How reliable is that tip? Is this guy someone who can be counted on? Or the noise. Is the information that you're seeing actually accurate and actually information that you need to be looking at? Things that you need to account for: a return distribution. How much variance is there in these returns? Is it that you're getting the same payout every time, or is the payout variable? An example of like, poker tournaments, where it has a power-law distribution, where if I play the main event for example, I expect to have a 200% ROI. Every time I enter into this 10k tournament, I expect to make twenty grand, but those returns are almost completely concentrated at the final table, which I'm only going to get to about 1% of the time. Which means I can play this tournament every year for the rest of my life and not make money on it. Right? So when the returns are heavily concentrated on the high upside outcomes, that means I should bet a lot less, because my chances of going broke or nearly broke are much higher.

The portfolio of bets. We saw this with the pairs trade. If you're making bets that are highly correlated you need to size down, because if one of those bets lose, a lot of those bets might lose. Right? We can see this in March 2020, when all correlations went to one. Crypto crashes went into market crashes, because people sell anything they can in a crash. So if your bets are very correlated you need to size down. On the other hand, if you're able to find anti-correlation or negative correlation, you can size up.

Another factor: what are the other bets that you have available to you? If you have really good deal flow, you might not want to bet as much, or taking into account the opportunity cost, right? If you're betting on—if you're putting 20% of your net worth into a bet that has a one-year lock-up period, what are the other bets that could come along that you cannot deploy capital into 'cause it's locked up? Right? There's liquidity cost there.

And then, just finally knowing yourself. Knowing your risk tolerance. And this might mean correcting up or down. Historically—this might surprise you guys given my profession—I think that I've been too conservative in my betting. That I have a pretty low risk tolerance overall. And so I know that, like—I try to use Kelly to encourage myself to bet larger when I know that I have an edge. If you have the tendency to over-leverage, then maybe you want to use this to set a limit, to correct down.

If you're interested in this, here are a couple more resources for you. I highly recommend the book, Fortune's Formula. This is kind of all the background that went into the creation of Kelly Criterion. It gets into like information theory, the wiring, arbitrage, knowing information before something happens, how did all of this come to be. It's essentially like a history of betting. Really well-written, highly recommend. The man who is featured very heavily in Fortune's Formula, Ed Thorp, wrote his own book applied to the markets which is also very good—applying Kelly Criterion to betting on public and private markets—it's called, A Man for All Markets. A book about the history of calculating edge and risk is called, Against the Gods. So going back to antiquity how we've determined how to put probabilities on things that are hard to estimate. Great read. And then finally this is a blog post by a friend of mine, Nick Yoder, which goes into different distributions using leverage on the Kelly Criterion. So if you want to model out for your own portfolio, that's a great resource as well.

Cool. Right about halfway in. I want to open it up to Q&A, so we can talk bet sizing. Here are some other things that I thought might be interesting to you. I talk a lot with clients about systems for decision-making. So things like pre and post-mortems, how to take results into account correctly to improve the decision-making process, things I think a lot about in terms of inner game. How do you manage your own psychology, cultivate your intuition, not blow up emotionally? Obviously, I think a lot about peak performance. How do you put yourself in the best possible decision to make great decisions on a daily basis? How do you create a life which maximizes your surface area serendipity, so you get lots of opportunity to invest, to cultivate that deal flow? And, yeah. If you want to learn more about kind of how I use poker to apply to investing, this is a very long, comprehensive blog post that I wrote this year called "Play to Win." That's the link.

With that, I'm gonna open it up to Q&A. I don't—if Tom, Kylie, you want to moderate. Just fire some questions my way.

Tom: One hundred percent, I'm happy to jump in here. And Hatham has a really interesting question about putting yourself in situations to strengthen yourself psychologically. Hatham, defer to you to ask the question.

Hatham: Yeah. Thanks for the presentation, Chris. I thought it was really cool. I see here the inner game part. You were talking about tilt and having guard rails. One way of kind of growing mentally was just to put myself in very, very bad situations mentally, and maybe not consciously doing it to be stronger, but I definitely feel like it can help over the long run. I wonder how you think about that. I know that when you play poker you probably find yourself in these situations often, so I just wonder what you think about that.

Chris: Yeah. I really love the book from Josh Waitzkin called, The Art of Learning. So if you're interested in this idea of going from the top 1% to the top .1%, that's a really good read. And he talks about this concept of training at altitude, where he was playing chess games in Russia, the Russians were playing super dirty. Kicking him under the table, like tapping the table to try to disrupt his concentration, outright cheating type stuff. And it would have been very easy to have been thrown off his game, but what he did was to play games in simulated conditions that were worse than anything he would face in a real-time game. I think of this as when I was playing baseball growing up, and the pitchers that I was facing were throwing seventy mile-per-hour fastballs, on average. And so I would go and hit in the ninety mile-per-hour cage, you know, mostly just completely whiff and occasionally hit a foul tip, but so that when I went back in that seventy mile-per-hour cage or faced a real pitcher, the seventy mile-per-hour pitch would feel slower. I wouldn't be fazed by it.

Obviously, there are lots of implications here for poker and for life as well: to train, right? Treat everything as an opportunity to practice, be stretching your muscles. And you don't want to be in a position that—generally the best times to invest, "blood in the street," like March 2020, when everyone's running around like a chicken with their head cut off, you need to be level-headed. Know what you're looking for, ready to go. A lot of taking advantage of these very ephemeral opportunities is being prepared for them and being able to function at a high level when they do appear.

I like to give this metaphor of a surfer. I'm going on a surf retreat next week in Panama, so it's very top of mind. A lot of people see surfing, and it's like, they see the highlights. But if you watch someone who's surfing all day, most of their day is just kind of paddling, and they get pushed by the tide and they have to paddle and get back into position, and in order to like catch these big waves that come, you need to be paddling. You need to be in position.

So yeah, so I think it's like a lot of investing is preparation. Both thinking of your thesis, but as well as just mental. Being able to be level-headed when these opportunities arise.

Hatham: Thanks.

Tom: I have a question. It's not directly related, but how do you know when you have edge? 'Cause like, I mean the easiest person—the key is to not fool yourself. You're the easiest person to fool. How do you know when you truly have edge? And it's a loaded question. There are so many ways to take it, and edge can take so many different forms. But I wonder if like, Chris, in your life you're like, hey. You thought you had edge, you didn't, and you did like a post-mortem on that. 'Cause I find myself thinking—but then when you think you're the smartest person in the room, that's when Dunning-Kruger really rears its ugly head. How do you know—is there a framework that you utilize to check that? I would love for you to go into that if you could.

Chris: Yeah. The classic saying in poker is, if you can't spot the sucker in the room, you're the sucker. And you know, any time that I sit down at a poker table, I know why I'm sitting down. I know where my money is coming from. And if there's not someone who is clearly worse than me who's putting money in play, I don't play. Your edge is diluted every time that you make a bet where you don't have edge. And as Warren Buffett puts it, investing is essentially like Home Run Derby, where you can just watch a million pitches go by until you have a super fat one, and then you swing. Assume that you don't have an edge almost every time. And the more efficient or competitive a market, and the more people who are looking after and studying it, the less likely you are to have an edge. Right? There are literally hundreds of people in the U.S. whose full-time job is to study Google. It's unlikely that you are going to have an edge betting on Google one way or the other if you are not doing it as your full-time job.

When I'm trying to figure out if I have edge, the biggest thing is I want to intimately understand who is on the other side of the trade. Right? Any time that you're making a bet, someone on the other side is betting against you. Remember our example of the guy on the other side of the road who is offering us 1.5 to 1 odds on a coin flip. Before I accept that bet for any amount of money that's going to hurt me, I want to understand why this bet is being offered to me. Right? I'm just a random guy walking down the road. Why did he pick to offer it to me? Is this guy a total troll? Did he just inherit a billion dollars and he wants to be charitable? Is he having fun? Is it rigged? Right? It's like trying to figure out, why is this bet available to me in particular? Who else has seen this bet and said, "No?" Do they know something that I don't? Is there someone that I can talk to to eliminate any blind spots?

Right? If I can understand why the person on the other side is offering the bet and I still want to take it, then that's really good. But if I don't understand why the bet is being offered to me, I have to assume that I am missing something.

I honestly think that bets of true edge are very, very rare, except for in areas that we have firsthand knowledge or experience. You're always looking for information asymmetries. What do you know that they don't? And if you aren't very confident that you have an informational edge, they likely know more than you do, and there's an adverse selection effect in play.

So really, finding bets where you have edge is just a function of getting access to lots and lots of bets. Right? The classic saying in VC is you get shown ten companies and you love one and you invest in one. Or you get shown a hundred companies and you love one and invest in one. The more deals that you're seeing, the more you start to cultivate your intuition around where are the places that you have edge. And the cool thing is that as you start to calibrate where you have that edge, you're able to trust yourself more and more over time. You're able to bet larger and faster because you have more proof of your own expertise. So if you're unsure, bet a small enough amount that you have some skin in the game in order to learn, but not so much that if you didn't have edge it's going to cost you.

I'll give a quick example. I backed a consortium of daily fantasy sports players where they didn't know who was on the other side of the trade. Right? They're facing a blind opponent. And so they're making assumptions about who it could be. If it's another pro player, they have to assume it's one of the best pro players in the world, and on average they're going to lose five percent. They have an edge of like, negative five percent. But if it's an unknown, some whale who just happens to want to bet six figures on a sports game, then their expected edge is twenty percent. Right? So every hundred dollars, they make a hundred twenty. So it needs to be a pro player on the other side over eighty percent of the time to not take the trade. Right? Because their edge is known, they're able to at least take a couple of these, and let's say if they take ten and it comes up a pro player nine times out of ten, all right. Let's stop taking that. But if it comes up a pro player like less than half of the time, let's back up the truck.

So you can see, by putting a little bit in play, being willing to take the worst of it in order to gain information, that can increase your confidence and allow you to bet larger as you're able to reduce your margin of error.

Tom: That is so, so useful. Just gold coming from your mouth. Honestly, Chris. Brendan has a question. Brendan, if you'd like to come off mute.

Brendan: Yeah, sure. I was just wondering like, if you could share a few of the life lessons you learned from going through Black Friday, and I'm sure—kind of the life upheaval that was for you as a pro poker player.

Chris: Yeah. I talk about this a little bit in "Play to Win." I was really taken off guard by it. Keep in mind I was twenty-three at the time. Didn't have a lot of life experience. And I was just making money hand over fist. So there were lots of signs out there that some sort of "black swan" event was possible. At the time, all of these player funds were getting seized, and the sites were just covering it and trying to cover it up. Right? They would have a payment processor that ran off with the money or got taken down by the Feds, and the sites would just cover it up and just give all the players their money. Or when I made a deposit on the site, it would show up on my account—instead of "Poker Starz" it would show up as "golfballs.com." It didn't take a rocket scientist to figure out that there was some clear money laundering happening. And at the time, the sites were spending forty cents on the dollar just getting money to and from players.

I would read these anecdotal stories because I wasn't directly affected, but obviously, there were some things going on that were being covered up. But because I was doing so well, I was so biased to think that these boom times would go on forever. And I had a very, very large percentage of my net worth on these poker sites on the day that Black Friday happened that got seized. Some of that for good reasons. For bankroll, I had some arbitrage opportunities, I was backing a lot of poker players, but I had just far too much money at risk, thinking it was just like a 0% bank account, and clearly, there were some counterparty risks there.

So one, I learned that when things are going well, you're very incentivized to overlook signs that the music might be stopping and there are not enough chairs for everyone to sit down. I also was very unhappy with the way that I handled Black Friday once it happened. A lot of poker players were even more aggressive with their bankroll management than me, and they had their entire net worth on these poker sites, and all of a sudden they had families and alimony and things they had to pay but no money with which to pay them, and this secondary market came up where you could buy people's balances for anywhere from twenty cents on the dollar to eighty cents on the dollar, depending on the buyer's trustworthiness. And I did neither. Right? I should have either been selling my balance at eighty cents on the dollar if I thought that I was unlikely to get paid back, or buying up a portfolio of other players' money at twenty to sixty cents on the dollar if I thought that they were likely to get paid back someday. And I did neither.

Part of it was I had over half my net worth in limbo, but the other part was it was too painful to try to calibrate to reality, and I just totally turtled up, went into a shell, started backpacking Europe to just get as far away from it as I could. And I learned that it's very hard to know how you're going to react in that situation until you're in it.

Fortunately—well, let's say unfortunately for the world, but fortunately for us as investors, I do think that these "black swan" events are gonna continue to happen, and they're going to happen at a higher frequency. So going through that experience in 2011 taught me a lot about how to react to an unexpected crash like this one, and because of my experience with Black Friday I feel like I was able to cover my downside ahead of the March crash in the crypto and the public markets. I was able to de-risk, de-leverage ahead of time. And even though I didn't redeploy right away, I redeployed a lot faster than I think I would have otherwise, without having that feeling of shell shock. Like, needing to deploy when you're at the peak of most fear, that type of stuff. So I think another lesson was just you get better at it every time. And knock on wood, we're gonna be investing for another sixty to eighty years, so we'll have lots of practice.

Tom: Amazing.

Brendan: Thank you.

Tom: I do wanna touch on something that you said, but I wanna let Ross ask his question as well. Ross, if you wanna come off mute, on camera.

Ross: Thanks for the talk. Just quick question, how should I think about like risk of ruin in the context of Kelly Criterion? Is it something that's necessarily different, or is the bound really the same thing? Like, is that how you think about making sure you don't end up with no bankroll? How should I think about that?

Chris: Sure. So, Kelly is designed that you cannot go broke, but you could approach going broke. And I always mispronounce this, in mathematics, it's like 'asymptote.' Right? You approach zero, but you never hit it. Right, hypothetically it could come out that, "Hey, you should bet ninety percent of your bankroll, this is such a slam dunk." But as everyone knows who plays in poker, you could be ninety percent to win, and lose five of those in a row. Right? And all of a sudden, you've lost ninety percent of your net worth five times, you now have like one percent of what you started. You haven't gone broke, but you've basically gone broke. And so something that we think about in the poker world a lot is that you never go completely broke as long as you have the social capital to borrow. Right? I can be a little bit more aggressive about bankroll management in poker because I know that there are a hundred people who would literally line up around the corner to stake me or lend me money should I need it, just because I have a long track record of both being a winning player and being a dependable borrower when I've been backed for big games in the past.

So like, there's losing your bankroll, and then there's going full broke as in you can't borrow further capital. This is also where risk tolerance comes into play. Right? Everyone discovers their true risk tolerance after a crash. Like, going into the recent fifty percent crypto drop, by the way. There were probably a lot of people who were like, "Hey, I'm up 10x. If I lose fifty percent at this point I'd still be okay." Well, they're probably feeling a lot different after experiencing a fifty percent drop. So even if the math comes out and tells you to bet twenty percent of your bankroll, being honest with yourself: how would you feel going from a million dollars to eight hundred thousand overnight? Would you still be able to think rationally with that? That's a lot of knowing yourself type calculations you have to adjust for.

Tom: Amazing. I have a question about something you said, Chris. You think that black swan events will continue to happen, but you said that you think they're going to continue to happen at a higher frequency. I'm interested in what you mean by that, why that's your thought, et cetera. Because that begets both trouble and opportunity, obviously, black swan events do.

Chris: Just, I mean, the observation that the timelines are much shorter. There's a lot more leverage inherent in the system, so any movements are both magnified as well as much more efficient. And just like things happen a lot faster, and they also correct a lot faster than they did. I also just think that over time, with entropy, we start to have very dispersive outcomes. So you know, all we have in investing is past performance, but as they say, past performance does not indicate our future performance. Who knows if like ten-year macrocycles or something that is just a historical aberration will continue? I am of the thought that these cycles will continue to compress and they will continue to be magnified on both peak and trough, which I think in general as an investor is an opportunity. For anyone who trades actively, you're essentially harvesting volatility.

Tom: That's awesome. Any more questions for Chris? This has been so elucidating. And if you're thinking it, someone else probably is as well. I know Chris, there's a joke, people are ready to bankroll—Joe has a question. Joe, fire away.

Joe: Yeah, I'll come off. I guess along the same lines, kind of expanding on that, how much of that is a black swan issue, or just the fact that it is increased volatility, because you have the algorithmic trading and all the things going on right now where you get, to your point, we get March 2020, but then like forty-five days later it's back up. So is it more—but the overall market's kind of trending up and to the right. So is it really an increase in black swans, or is there just more volatility between the black swans because of how fast things are moving these days?

Chris: It's a complicated question. I mean, first I'm such a massive Taleb fanboy, and I think there's a lot to learn there as far as seeking positive convexity and avoiding opportunities that, you know, as far as they can be known where you're completely exposed. I do, however, think that this whole notion of a black swan is very lazy thinking. I think a lot of these things that we post-hoc label black swans were very preventable and predictable but it allows us to just move on just by saying, "Oh yeah, that couldn't have been predicted, what could be done?"

So there's also just an inter-connectivity to everything. I love this concept of a container, right? Thinking of like the Titanic, where supposedly if one of these containers was breached, it could spill over to the other containers, but now it like—for lack of a better way of putting it, the world is extremely flat, and the butterfly flapping its wings in Chile affects us here in the States. Everything is part of this massively complex adaptive system which is a total black box with complete emergent effects, so all of these small emergent conditions are just super-magnified in today's global economy. So yeah, I mean I think that's the sort of thing that I'm talking about, there are just far more catalysts at play, and that because of the complexity of inter-connectivity, all of those emergent effects are just magnified.

But, asterisk, I'm not a professional. So that's just my opinion.

Tom: That's a—I totally feel that. Any more questions for Chris before we give him a warm round of applause? I have a question if no one does. Chris, if people want to reach out, if they want to find you, if they want to engage you for coaching or read more of your stuff, where can they do that?

Chris: Yeah. My company is Forcing Function. That's forcingfunction.com. Some good resources on there. We have a workbook which details all of the things that I advise my clients to do. That's free to download. So, forcingfunction.com/workbook. I have a client waitlist until October. If you want to get on that waitlist, you can go to /coaching. The best opportunity if you're interested in what we're doing and wanna work together is we offer a group class twice a year. The next version of that class is kicking off in [February]. You can learn more about that at teamperformancetraining.com. And yeah, I recommend reading "Play to Win" if you want to know my thinking on this stuff, applying poker to investing. You can PM me in the ODI Slack.

Tom: Amazing. Can we all come off mute and give Chris a warm round? This was thrilling. This was awesome. Thank you, Chris. Coming to us live with the iPhone and camera and webcam situation. I love it. There are two Chris Sparks in the chat. And that's—two Chris Sparks, not enough. Let's put it that way. Thank you so much, everybody, and have a great rest of your Thursday.